Writing

Looking for inspiration, design tricks, how to make a great cover, promoting your yearbook and engaging your community?

Most recent

10 people to thank

‘Tis the season to show appreciation. A quick internet search nails myriad resources outlining how regularly expressing thanks can positively impact one's mental health and overall well-being. That’s why we created the yearbook thank you shortlist.

Below are ten people to thank who may have made a significant impact on the yearbook students' productivity:

- Custodial and maintenance team: Appreciate the custodial and maintenance team for their hard work maintaining a clean and functional school space, which creates a conducive environment for creativity and collaboration.

- Administrative staff: Extend thanks to the administrative staff for their behind-the-scenes efforts in answering all the, "Did I buy a yearbook?" calls while serving as veritable who's who for campus activites. Seriously, every campus has that one seasoned staff member who knows all the kid's names and helps you proof the yearbook, and chance are she's running point in the front office.

- Teachers: Thank teachers and instructors who opened their doors for yearbook interviews and shared photos of their classroom happenings. They're the yearbook heroes who pitch their upcoming projects and presentations as photo oppportunities, and they use the Treering App to upload great pictures from their field trips.

- School librarians and media specialists: Thank the school librarian for their assistance in research, providing valuable resources, and supporting the yearbook team in gathering information and materials, including tech tools.

- Principal and assistant principals: Express gratitude to the admin team for their leadership, support, and commitment to fostering an environment where creative projects like the yearbook can thrive. (Bonus points if the principal and/or AP also ensure the yearbook photographers get good angles for snapping action shots during fun school events.)

- Cafeteria staff: Thank the cafeteria staff for their role in keeping students well-nourished and providing energy and sustenance during busy yearbook project periods.

- Parents and guardians: Extend thanks to those who bought their book by the deadline for supporting history-in-the-making with the yearbook, that mom with the nice DSLR camera who is at all the events taking great pictures, and the parents who added 30 extra custom pages making their childrens' books double the size!

- Anyone who responded to a crowdsourcing request: Express thanks to the contributors for their valuable insights, diverse perspectives, and the depth they brought to the yeabook.

- Student body: Express thanks to the entire student body for their active participation, cooperation, and enthusiasm, making the yearbook a true representation of the collective experiences and memories of the school year. (We're talking to you, middle schooler, who thinks it's so "cringy" when your mom is on campus taking pictures for the yearbook that you won't even wave at her. You'll thank us later.)

- Yearbook publisher: Acknowledge the service, printing, and production teams for their hard work in bringing digital designs to life, ensuring your school's yearbooks are of the highest quality.

To demonstrate gratitude, your yearbook team can write a card, decorate a gratitude wall in the hallway, or sponsor a lunch or coffee hour.

Using the "five common topics" for yearbook copy

The inverted pyramid is the go-to launch point for budding journalists. (Anyone else hear a journalism teacher’s voice: “Don’t bury the lede!”) For these emerging writers, filling each level equates to squeezing the five Ws into its ranks. This could lead to repetitive or restricted writing. The “easy” fix: asking better questions.

Integrating the five common topics with the inverted pyramid structure helps students create engaging yearbook copy because it models inquiry. They move beyond “What was your favorite…?” They create questions with analytical depth. They craft stories worth reading.

What are the five common topics?

How would the ancient Greek and Roman orators write a yearbook story? (That might as well be under “Adviser questions I’ll never ask for 1000, Alex.”) The five common topics are definition, comparison, relationship, circumstance, and testimony. The early scholars used this method of inquiry to discuss, persuade, and analyze. Developing yearbook interview questions based on the five common topics can be a structured way to gather information and insights.

Definition

The five Ws fall here: the topic of definition breaks down your subject into key components. What it is and who does it. Where it takes place. Why it’s important. When it occurs.

What is a clear definition of [the subject]?

This is extremely helpful for students when they craft copy on an unfamiliar topic. For example, most people use “bump, set, spike” somewhere on a volleyball spread. We don’t bump. We pass.

How would you characterize the key features that distinguish [the subject] from other similar concepts?

Each game, dance, movie night, and fun run is unique. So are labs, presentations, debates, and study sessions. Find out what sets this event or activity apart. By defining what it is holistically, you are also defining what it is not: just another day. (Remember, there is a reason for this story beyond an opening in your page template.)

What are the essential elements that makeup [the subject]?

Sports and arts copy can always be improved by understanding the technique. Start with your photos and ask the stakeholders to explain what they are doing step by step. Define tools, from cleat spikes to microscopes, and their use.

Back to our volleyball example: She’s aligning her feet to the setter and positioning her body so her belly button is behind the ball. Straight arms and little-to-no movement are key for her to give a high pass the setter can push to the outside hitters or run a quick hit from the middle. She starts each practice by passing 50 free balls as an offense-defense transition drill.

No bumping is involved.

Comparison

The next step is to expand upon the basics by drawing parallels or highlighting differences. Using analogies, journalism students can make complex ideas understandable. Sometimes, it helps to take the opposite approach and point out key differences.

In what ways is [the subject] similar to [another relevant entity], and how are they different?

Familiarity is comfortable. By relating new topics to known ones, you can ease your reader in.

Are there instances where lessons from [a related concept] can be applied to [the subject]?

Again, even though chemistry class repeats the gummy bear lab annually, it is not the same year after year. The same can be said about an AP class preparing their art portfolios or a Link Crew orientation.

Using the topic of comparison, student reporters have a reason to cover recurring events–they are digging into the differences.

How does the comparison to [another relevant entity] enhance our understanding of [the subject]?

Keyword: enhance. Comparison is valuable if it adds value. And before you flinch at the intended redundancy, remember new writers need to evaluate their notes as part of their process. Listing related and opposing concepts will also strengthen the topic of definition.

Relationship and Circumstance (This is a Twofer)

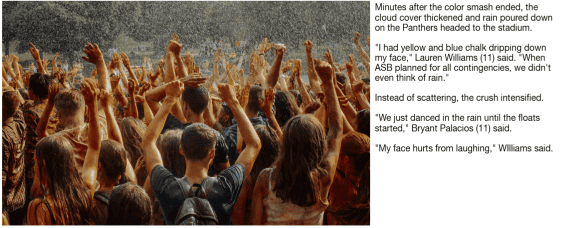

I’m combining topics three and four. Event sequences, cause-and-effect relationships, and the outcome of the event all have a place at the proverbial table. Understanding circumstance helps in tailoring yearbook copy to be more relevant and effective because we use it to examine the context of each story. It’s the here and now. These details help readers understand why the event is significant at this moment.

What current events or trends are influencing [the subject]?

More than the water bottle du jour, the timeliness of a yearbook story gives its place in your school’s historical record. You give campus events context by relating them to the community or even the world.

Are there specific challenges or opportunities related to [the subject] that are particularly relevant now?

In the example above, a student gave a speech. This is a daily occurrence around the globe. The author used the subject’s reported challenges and testimony (spoiler alert: that’s topic #5) to illustrate what led to the moment.

Chances are, this story wouldn’t have been printed in your mom’s yearbook. The circumstance was different.

Can you identify any cause-and-effect relationships associated with [the subject]?

Part of contextualizing your yearbook stories is adding what resulted from the story. Did the fundraiser set a new record? Athlete return for her final game of the season? AP Language class win the literary food festival? Wrap up your story.

Testimony

“Give me a quote for the yearbook.” Next to definition, testimony is the most commonly used of the five common topics. It’s the human element. Including testimonies from different sources helps balance the story, gives authority to student writing, and showcases varied perspectives.

While it’s the fifth topic, when students write, they should incorporate the questions below.

What diverse perspectives contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of [the subject]?

Scores, stats, fundraising figures, and meaningful quotes enhance credibility and give voice to yearbook copy.

How do you navigate conflicting testimony or opinions from authoritative sources regarding [the subject]?

The short answer: ask more questions. How do you find out what is true and who do you ask? (This could be more common with sporting events over bio labs.)

Testimony: Add relevant quotes from participants or spectators to illustrate.

Relationship and Circumstance: Explain what factors led to the event and how it impacted the school community.

Testimony: End the story by adding additional quotes or data to add depth and credibility.

Example structure for the inverted pyramid and five common topics

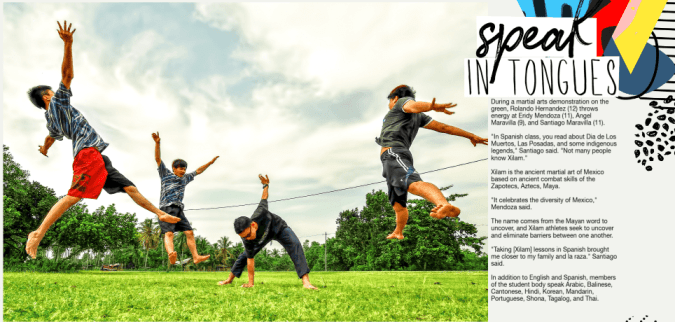

Let’s start with this photograph of four students on the green.

To come up with the copy, students identified:

- Names of students and their grades

- Location of photo

- What is going on

- Background on Xilam

- What aspect of Xilam is shown in the image

- Relationships between Mexican martial arts and Spanish for native speakers class

- How many languages–and which ones–are spoken on campus

This structure delivers both the essential information layered with insights. It moves beyond a listing of the 5Ws because it begins with inquiry.

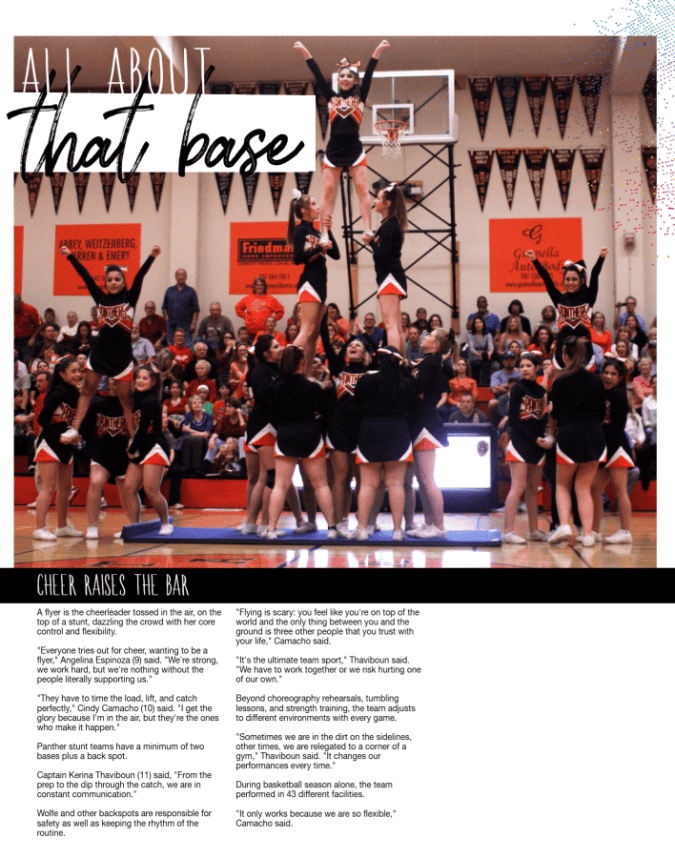

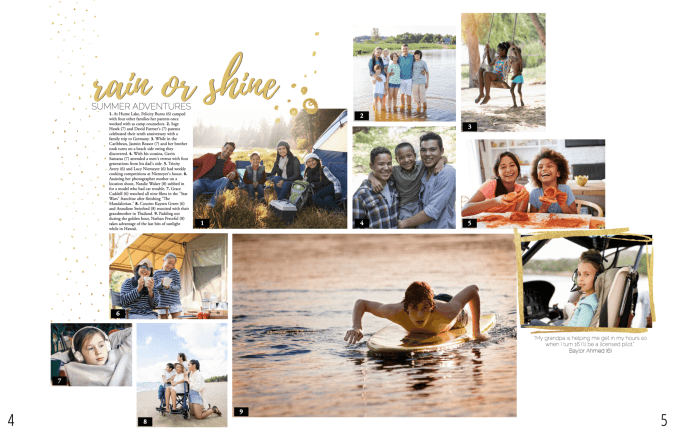

Caption this: writing tips for yearbook

Yearbook captions provide the context and information to help tell the story behind each photo. They explain what's happening, who is in the picture, and why it's significant. Without captions, many images may lose their meaning or context. Conversely, it is not a storytelling photo if you cannot write about it.

Try this: open your middle school yearbook and try to name all the people on page 24. Can you do it without looking at the captions?

Three types of yearbook captions

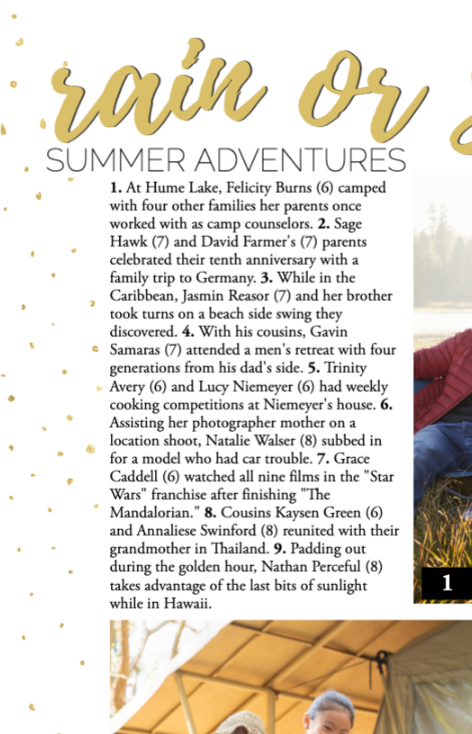

Ident captions

Also, called ID captions, they do just that: identify who is in the photograph. Often used in photo collages, ident captions preserve the names of individuals for posterity and historical record. At a basic level, knowing the names of the individuals can make the yearbook content more personal and relatable, and, from a student’s point of view, their name equates to their mark on your campus community.

Summary captions

These captions tell a brief story or narrative related to the photo. They engage the reader by presenting the photo as part of a larger, unfolding story by answering who, what, when, why, where, and how in a sentence. Summary captions are always written in the present tense.

Start by being Captain Obvious and use the why and how to give readers more information.

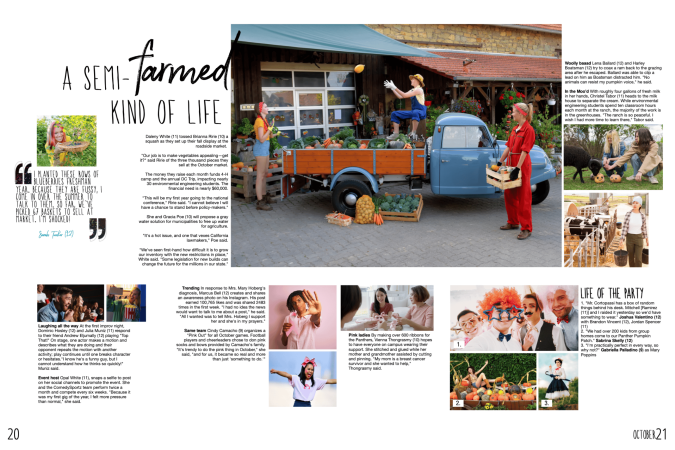

Expanded captions

Writing an expanded caption for a yearbook involves providing more context and detail about the photo. It’s journalism. It requires practice. It’s a skill. Each expanded caption is a three-sentence story that adds depth to your spread and supports the whole year’s narrative.

Expanded captions have three parts, four if your yearbook has a lede.

How do I write expanded captions?

Because writing is a process, each of the following steps takes time and attention to be effective.

Step 1: observe and analyze the photograph

Identify key elements, people, objects, and actions using who, what, when, why, where, and how. Be sure to consider the emotions, expressions, and details within the foreground and background of the image.

Verify names and activities before moving to the second step.

Step 2: prepare interview questions

Use open-ended questions to gather more information, opinions, and insights from individuals. Find out what happened before and after the photograph and the relationships between the people in the image. Remember, it’s better to have to cut down content than scramble to fill space.

The goal of your interview is to provide additional context and meaning. Showing up and saying, “Give me a quote for the yearbook,” isn’t going to achieve that.

Step 3: put it all together

What not to do

Avoid editorializing and jokes. It’s not your job to critique what is happening (Romero’s awesome painting) or change the narrative (Is that Bob Ross? No, it’s Ezekiel Romero). Your job is to report. Quotes should be used to convey the feelings or reactions of the people involved.

Get more caption help with the writing module in Treering's free curriculum.

By adding captions—ident, summary, or expanded—you not only describe the photo, but also provide a deeper understanding of the moment and its significance, making your yearbook more engaging and informative.

Why I stopped publishing senior quotes

Unpopular opinion: senior quotes are problematic because they are unoriginal and full of risk. Before you click away from this perceived pessimistic view, put on your journalist hat and look at the facts. This position is not an anti-expression rant but a push to develop original, authentic content for our yearbooks. Here’s how I replaced senior quotes 15 years ago.

Three reasons to start a new senior tradition

1. Participation and originality

A struggle we see from advisers is a small percentage of students submit their senior quote. Those who do use a quote from a movie, song lyric, or timestamp, not their own thoughts. That’s not journalism. These pop culture references may have a place in a module or personality profile elsewhere in the book if it relates to your theme.

2. Vetting process

Do you know the periodic table? Are you fluent in slang, TikTok trends, drug euphemisms, and veiled sexual references? Does your district have a hard line on what is free vs. hate speech?

3. Senior quotes can equate to bad PR

A quick news search for "yearbook senior quotes" yields myriad results of senior quotes gone wrong. Allegations of bullying in the yearbook and “unlawful accessing” the online editor abound. Schools have even cut the pages from their books due to the quotes in print.

Ideas to replace senior quotes

Thanks for sticking with me. Below are ways to celebrate the seniors on your campus and capture their voices (rather than Michael Scott’s).

Brag sheets

If your seniors want to leave their proverbial mark, include their school contribution with their senior portrait. A Google Form listing all the activities, clubs, and teams offered on your campus makes it quick for students to click through. Partner with a department and ask for it to be the bell ringer or exit ticket for a day.

You could also include class stats, such as athletic participation rate, percentage of students in leadership, and volunteer hours.

Include more quotes with expanded captions throughout the book

If your yearbook program is journalistic, it should have storytelling and reporting at its heart. Expanded captions include direct quotes. By using them, you are creating a yearbook full of original voices and senior, junior, eighth grader, etc. quotes. Here’s how it works:

- Identification information: who is doing what when and for what purpose? (Use present tense.)

- Secondary information: what is something you wouldn’t know from looking at the photo? (Use past tense.) This could be the result of the play or experiment pictured or the relationship between the students.

- Quote and attribution: include a direct quote from the subject that adds emotion, opinion, or information that isn’t obvious. Identify the quote with last name (grade) said.

Create a survey based on thematic coverage

Theme is king in yearbook. You selected it because it was the guiding story and look for your book. When you are developing your theme, create interview questions using this language.

For example, Rock Academy’s theme “Give + Take” yielded interview questions such as “What’s your take?” or “Give me five…” (songs, class activities, places you go on campus, etc.). Pro tip: use an idiom dictionary to search for such spin-offs for your theme.

For their book “Speak Life,” Sequoia High had a running module throughout the book called “Speak Your Piece” with quotes from students about a specific moment.

Sell ad space

Yup. I said that. When you pay to play, there is a little more consideration and propriety. Some schools offer 1/8 page to all their seniors and give parents the option to pay for upgraded space. (You'll have to get creative with the alphabetizing.) Others create a section with the index to feature ads.

With Treering Yearbooks, families also have two free customizable pages that print only in their book.

Stay the course

Full disclosure: my first year, there was a little heat from students and a petition. By year two, students (of all grades) saw their voices in every corner of the yearbook, and no one questioned it. The standard response became "We have senior quotes on every spread in the yearbook."

Why you need evergreen content for yearbook

Like its namesake, evergreen content stays fresh for a long time, unlike the tie-dye loungewear we are still trying to forget. While you should definitely include polls and trends in your yearbook (it is the story of the year after all), open-ended interview questions (such as the 40+ we are giving you below) should remain in your repertoire for three reasons:

For ease of use, we organized these interview questions by yearbook section. Grab your editorial team and create your list!

Student Life

Because some of your formative moments occur outside the classroom, be sure to include all that goes into the school day.

Campus Life

Routine

People

These questions make great sidebars to go along your portrait pages.

Milestones

Interests

Academics

Athletics

Bonus: Trending Topics

Add content on the following to complement the evergreen content in your yearbook.

For even more interviewing tips, check out the yearbook storytelling module from Treering's free curriculum.

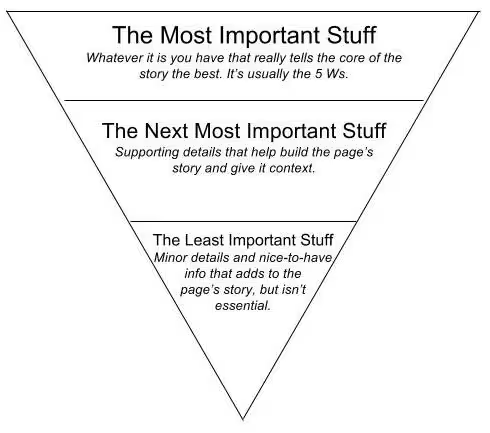

Why your yearbook writing needs the inverted pyramid

The easiest way to hook your reader is to use a yearbook writing technique that’s used by the pros: Put the most important stuff first.

You and your yearbook team have limited time to capture a reader’s attention—and, perhaps more importantly, limited space to tell your story—so you should be focused on hitting them with the big stuff right out of the gate.

In journalism, this writing technique is known as the inverted pyramid. In military and government briefs, it’s known as BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front).

Because the yearbook is journalistic in nature, we’ll be sticking with the term “inverted pyramid” throughout this post. But know this: Whatever you call it, the technique is an effective means of communication. And it’s one your team can use when looking to improve its yearbook writing.

Inside this post, we’ll walk you through what the inverted pyramid looks like and how you can break it down into manageable chunks.

What the inverted pyramid looks like

When it comes right down to it, the organization of your yearbook writing should look like this:

That’s an inverted pyramid.

It’s a three-tiered writing diagram that forces the most important stuff to the very top and the remainder of the story’s details into the two remaining tiers.

How to use the inverted pyramid in your yearbook writing

This approach to yearbook writing might sound obvious (or maybe even boring), but plenty of student journalists will try to tell a story in chronological order. Help them avoid that by showing them this diagram.

Put the most important stuff first

Your opening lines, or the lead, as it’s often known, should immediately state what’s special about the article. What was different about the event this year as opposed to last year? What makes this story noteworthy?

The lead should cover most of the five Ws: Who, What, When, Where and Why. These elements provide the biggest, most important pieces of information, and should be introduced early in your article.

The more interesting the news, the more reader will want the details. You’re not writing a mystery novel, so don’t try to tease your audience with page-turning suspense. You’ve got a limited time to capture their attention, so hit them with the big stuff right out of the gate.

Put the next-most important stuff second

Now that the reader is invested in the story, this is a great space to share more about the event or achievement, and the students that were involved.

After reading the headline and the lead, readers will get the basics of what happened. The middle section is your opportunity to tell more of a story. You can also expand a bit more on the how.

You can do this in a few ways, but some of the most proven tactics include:

- Relying on first-hand accounts. Relying on interviews with students and participants can help you paint a picture of what an event felt like to those who experienced it. Quotes, in particular, can help evoke emotion, which is a strong way to keep readers engaged.

- Including background details. If you can continue to build on your 5 Ws, all the better. Background details, like the time left on the clock when the basketball team scored the championship-winning basket or the number of hours it took the stagehands to build the set for the school play, helps propel a story along and give the reader a deeper understanding of what happened and why you’re writing about it.

- Using pull-quotes. Really great quotes can do more than just evoke emotion. They can also be used to break up text and add some design elements to your page or spread. Think of a pull-quote as another entry point for the reader.

Just as in the overall structure of the inverted pyramid, the middle section should begin with the most important details, and cascade down to the less essential stuff. There aren’t clear breaks between beginning, middle, and end sections, so you don’t have to worry about where one section ends and the next begins.

Put the least-most important stuff last

If you’ve really captured your reader’s attention, they’re going to be hungry for every little bit of information they can get. (You know the binge TV watcher who seeks out fan forums online? Or the Belieber who knows lyrics to the songs that didn’t make Justin Bieber’s album? That’s the type of reader who stays until the end.)

The more you can attract an audience with the big hits, the more you can interest them in the details.

Details that would otherwise be left out belong at the end. They might be interesting, but if you need to cut them for space, it’s no big deal. Of course, you’ll want to leave the readers satisfied, so if you can finish with any kind of pithy or clever line, that will make them more likely to read your next article from start to finish. A retrospective or forward-looking quote from a student is also a nice way to draw each piece to a close.

Chances are your pages won’t be filled with text, but you’ll want to share what you’ve got in a way that makes sense. If you follow this simple formula, you’ll not only be able to highlight the year’s most memorable moments, you’ll also develop a clear and valuable method of yearbook writing from top to bottom—and that’s the point.

Making yearbooks more accessible with opendyslexic

Fonts can be the Marsha Brady of the yearbook world. Overshadowed by epic theme packages and color palettes, the power of typography cannot stay silent. (In fact, the correct font can be louder than your graphics.) With 44 new fonts in the Treering catalog, you can share your story with boldness or a touch of whimsy. It can be focused or zany, handwritten or high-tech.

“Typography, like other design elements, evolves over time. Keeping up with current trends ensures that your designs feel fresh, relevant, and aligned with contemporary aesthetics,” Treering’s Director of Design, Allison V. said. “Typography also strongly impacts how a message is conveyed and perceived. More importantly, we listen to our users and try to accommodate their needs and wants. We often receive requests for fonts and appreciate the input from you.”

One such request came in the form of a text.

Meet OpenDyslexic

Since origin stories are a big deal in the superhero world, here is OpenDyslexic’s: app and game designer Abelardo “Abbie” Gonzalez developed the font in 2011 to help people with dyslexia improve their reading experience.

OpenDyslexic’s design addresses common challenges faced by many readers with dyslexia:

- Letter Weight: OpenDyslexic uses a slightly heavier letter weight, which helps the letters stand out more clearly on the page and reduces letter crowding. When designing for readers with dyslexia, avoid using italics or underlines because they cause letter crowding.

- Bottom Heavy: The base of the letters is slightly thicker, which provides better anchoring for letters. This can reduce the chances of them being flipped or reversed.

- Distinct Letter Shapes: The font uses distinct letter shapes to minimize letter confusion, such as avoiding mirror-image similarities between letters like "b" and "d."

Because it’s an open-source font, it is freely available. You can even make it your web browser’s font.

How would you use OpenDyslexic in yearbook design?

The short answer: headlines and captions.

The British Dyslexia Association and the UX Movement established Dyslexia-Friendly Style Guides. Summed up, the following tips can increase the readability of your spreads:

- Modular design: use negative space to break up content into meaningful chunks

- Keep backgrounds to a single color, ideally cream or pastel peach, orange, yellow, and blue

- For text, ensure there is contrast between the background and words on your yearbook spread

- Left align text

- Use font size 12-14 pt.

As with anything, it is essential to note that while dyslexia-friendly fonts and design can be beneficial for some individuals, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for all learners. If possible, seek stakeholders' feedback during the design process to identify potential improvements.

75 awesome yearbook interview questions for students

The best way to fill your school’s yearbook with hilarious anecdotes, memorable quotes, and cultural relevance is to ask your students the right yearbook interview questions. Great questions can unearth great stories from seemingly the most "boring" places, give you a fresh perspective on an old, tired subject matter, and quickly highlight for you the biggest trends among your student body. But you can't do that with boring, binary questions. Yes or no answers are only compelling en mass and repurposed as visuals. They lack the idiosyncrasies and personality that make a yearbook come to life.

To get the right results, your yearbook interview questions need to be open ended. They need to force people to explain their answers. They also need to have a purpose.

Inside this post, we'll walk you through the three types of yearbook interview questions and how you can use each. Then, we'll get to the good stuff: 75 ready-made questions you can use to interview students and improve your yearbook. Right now.

Still unsure of what to ask your students? Looking for a place to get started? We’ve got you covered.

What types of yearbook interview questions really work?

There are three types of questions you should be asking in student interviews: surveys, anecdotes, fishing for quotes. SurveyThese are the lifeblood of your book. Questions can range from “what was the song of the year?” to “which member of your class would win the presidential election?”. These are fun questions, great for putting students at ease, for building trust before asking them to share personal opinions and anecdotes.

Here, you’re looking for stories. Once a student is comfortable (after you’ve asked survey questions), you’ll want to ask questions that will elicit elaborate responses chocked full of personality. The more long winded, the better (they can be culled). Asking for anecdotes won’t just give you unique insights from the student perspective: it’ll give you insight as to the events that demand more coverage from yearbook staff, too.

Distilling your school’s most important events into tweet-length bits gives your yearbook some punch. It’s likely many of them will be hilarious, not serious and that’s okay: quotes don’t have to be profound, they just need to capture moments. Who knows: maybe a student will say something that perfectly captures your school’s milieu this year. Whatever you do: avoid yes or no questions at all costs. Binary questions devalue opinions in favor of convenience; only the most gregarious students will overshare. You want your yearbook to be diverse, offering as many different personalities as it possibly can.

Yearbook Interview Questions: A Complete List

Without any context, your yearbook is just a photo album. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Pictures are great. They’re absolutely the first things students will look at. But aside from a few amazing images, they're not the stuff people are going to talk about. It’s the written context—the stuff people read and learn when they open the book—that really resonates.

To get that, you need yearbook interview questions that will get your students, teachers, coaches, and administrators to open up. Here are 75, separated by category, to get you started:

High School Student Life

- Do you drive to school? What was your most listened to driving song on your morning commute this year?

- Which school tradition are you most proud of?

- Would students be more productive if cell phones were banned during school hours?

- What’s your favorite school lunch?

- Should the school have (or keep) vending machines?

- Do you think an open campus is a good idea?

- What’s your most embarrassing in-school memory? What happened and did you learn anything from it?

- Which event did you most look forward to this year? Did it live up to expectations?

- You can bring any three of your classmates on a cross-country road trip in your family’s hatchback: who would you choose and why?

- If you could get rid of the bells between classes, would you? Why?

- How did you decorate your locker this year?

- How do you avoid participating in gossip? What do you do if there’s gossip about you?

Elementary school student life

- Which event at field day was the most fun?

- What was the coolest art project you did this year?

- If your school grew and maintained its own vegetable garden, what would you want to grow?

- If you could plan a field trip anywhere for next year, where would you want to go?

- How do you like to read? (physical books, Kindle, etc.)

- What’s your favorite kind of juice?

- If you and your friends could do any activity after school today, what would it be?

- What’s the best game or sport that you play in gym class? Why is it so fun?

- What’s your favorite school snack?

- If you could choose any animal for a class pet, what would it be?

Sports

- Which team’s games are the most fun to attend? Why?

- If you could have the pep band play one song at games, what would it be?

- Describe your crosstown rivalry in one (appropriate) word...

- Which sport does the school need to add next year?

- If anyone in your class would be on ESPN, who would it be?

- What was the most memorable school sporting event of the year?

- How does playing X impact your academic performance?

- What life-lesson(s) did you learn playing X?

- Will you try to play X in college?

- Would you ever consider coaching?

Clubs

- Do you think participation in extracurricular activities should be required by the school?

- If your club was given an unlimited budget to throw an event for the school, what would you plan?

- Should video games be considered a sport? Which games? Would you join a school eSports team?

- If you could create one new club for next year, what would it be?

- Who’s the best club adviser?

- Where does your club meet? Do you use any school resources other than space? How could the school provide more support for your club?

- Which plays should the school produce next year? Would you audition if it was something you liked?

Academics

- If you could choose any artistic medium and give it a dedicated course, what would it be?

- The jobs you will have one day don’t even exist yet: what kinds of skills do you think you might need to succeed?

- Least memorable United States President?

- Are there enough foreign language options? If not, what would you like to see added? Should they be required?

- What project or assignment challenged you the most as a student? Why?

- Most useful math equation or theory you learned this year?

- What was the longest paper you wrote this year? Who was it for? What was it about?

- If you could conduct any science experiment in a class, what would it be? Do you have a hypothesis ready to go?

- What was the most enjoyable book you had to read for school this year?

- Which subject do you think prepares you most for life after high school? Why?

Pop culture

- Which TV show is most talked about in the hallways?

- What would you be SO embarrassed to be seen wearing (but secretly love)?

- Which meme/gif did you use most frequently this year?

- Which movie that came out this year would you be most embarrassed to watch with your family?

- Which professional sports team were you most excited about this year?

- Which presidential candidate would you vote for?

- If you were in charge of planning a concert for the school, which three artists would you bring?

Technology

- What’s your favorite Snapchat/Instagram filter?

- Most social media savvy teacher?

- How can teachers make social media part of their curricula?

- If you could only use one emoji for the rest of high school, which would you choose? (Be sure to check these for appropriateness.)

- Do you have your own website? How did you make it? What do you use it for?

- Which piece of technology has most contributed to your academic success?

- What was the most “viral” event of the school year?

- How would you recommend the school use its technology budget? What kinds of devices or software would you like to see available next year?

- Would you be more likely to read or contribute to the school newspaper if it was digital?

- What’s your favorite podcast? Is there any way teachers could incorporate it into their classrooms?

Seniors

- If you applied, when did you start your college applications?

- What made you decide not to go to college next year?

- Describe your senior year in three words.

- If you could create one mandatory course for future seniors, what would it be?

- “I will always remember…”

- Should there be a community service components involved in graduation (X number of hours, a project, etc.)?

- Who was your favorite teacher throughout all of high school?

- If you could change one school rule, what would it be?

- Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

Teaching yearbook: 60 bell ringers

How different would your yearbook class or club be if you had ten minutes at the start to focus your team on the day's objectives and transition them from hallway to classroom mode? Working with middle and high school yearbook advisers, we created 60 Bell Ringers to do just this. Use the prompts below to teach and strengthen skills by dropping them in Google Classroom, displaying them in a slide deck, or writing them on the board.

- Why Do You Need Bell Ringers for Yearbook?

- Teambuilding

- Bell Ringers to Teach Writing

- What’s Happening Here?

- Brainstorming Bell Ringers

- Use These Bell Ringers to Model a Yearbook Critique

- Writing Prompts for Reflection

Why do you need bell ringers for yearbook?

While we often pump the intro to design and copywriting lessons the first few weeks of the school year, the overwhelming nature of organizing photo shoots, liaising with club sponsors or athletic coaches and scheduling picture day take precedence. (Validation: those things are vital for the success of your yearbook–keep doing them!)

If you’re submitting documentation for WASC or your admin, bell ringers activate learning by giving students a quick thought-provoking question, problem-solving exercise, or yearbook critique activity. Some bell ringers encourage critical thinking, and others serve as an anticipatory activity because they stimulate students’ curiosity.

TLDR? Use bell ringers to set the tone.

Teambuilding

Yes, you’ll have your group games, yearbook weddings, and human knots. And no, that’s not all you’ll need to forge connections and build trust. These prompts help students share and learn about each other’s interests, preferences, and experiences and teach empathy for those they’ll interview in the weeks ahead.

- “Emoji Introduction”: Share three emojis that represent different aspects of your life. (Afterward, students share their emojis with the class and explain their choices, providing insights into their personalities and experiences.)

- “Time Capsule”: Describe five things you would put in a time capsule for yearbook students 10 years from now.

- “Do-Over”: What is one thing you wish you had done differently this year and why?

- “Influencer”: Share a book, movie, or song that profoundly impacted you and explain why it resonated with you. (If appropriate, you may want to create a yearbook team playlist for motivation, or when it’s time to celebrate good times… come on!)

- “Self-Promotion”: What role does the yearbook play in fostering a sense of community and collective identity within the school? How are you contributing?

- “Dear Younger Me”: Reflect on your overall personal growth and development throughout your time on the yearbook staff and how it has shaped you as an individual. What did you wish you knew at the start of the year?

- “Mind Shift”: Describe a class or subject that you initially didn’t enjoy but ended up loving and why your perspective changed.

- “Second Life”: What is something you are proud of accomplishing outside of academics this year?

Bell ringers to teach writing

Quick math lesson: one five-minute writing bell ringer debrief a week will give your students an additional 200 minutes of writing practice. With these short writing tasks, advisers can also provide more immediate feedback to students when they share their work. Don’t think of it as an informal assessment that requires a line item in the grade book, but rather as facilitating continuous growth.

Ledes and captions

- What is the importance of a compelling lede in a piece of writing? Share an example of a lead that successfully captures your attention and explain why it stands out to you.

- Think about a memorable article or story you’ve read recently. Analyze the lede and discuss how it effectively hooks the reader and sets the tone for the rest of the piece.

- Choose a recent photo from your phone and write three possible ledes: one pun, one using your theme, and one three-word attention-grabber.

- Reflect on a nearly finished spread and revise at least one lede. Share how it improved the overall impact of your writing.

Feature stories

- Think about a significant moment or event from your school year that you believe would make a great yearbook story. Outline the key elements of the story, including the people involved, the emotions experienced, and the impact it had on the school community.

- List potential angles, interview questions, and storytelling techniques you would employ for a personality profile for a student you do not know.

- Interview another yearbook student about a personal experience or accomplishment from this school year. Write a brief summary of the story, including the central theme, key moments, and the message or lesson it conveys.

- Brainstorm ideas for a yearbook story that celebrates the diversity and inclusivity of your school community. Share potential story angles or interview questions that would help capture the richness of your school’s diversity.

- Have students gather in small groups and share one memorable experience or event from the school year. Each group should choose one story to develop further as a potential yearbook feature. Encourage them to discuss the key moments, people (directly and indirectly involved), emotions, and impact of the story.

- Provide students with a collection of unused photographs from a specific school activity. In pairs or individually, students should select one photo that catches their attention and write a brief story idea based on the image. Encourage them to consider the context, characters, and potential narrative elements.

- Organize a “Story Pitch” session where students can present their yearbook story ideas to the class. Each student should prepare a short pitch, explaining the central theme, key moments, and the significance of their chosen story. Encourage constructive feedback and discussion among the students.

What’s happening here?

These yearbook caption bell ringers work best when paired with a photo of a prominent event on campus or one from history or pop culture. The goal is to unpack the action and the story within the image. For consistent practice, make a weekly event, such as “Photo Friday,” to cycle through these prompts.

- List the who, what, when, where, why, and how of this photo.

- List 10 or more verbs to describe the subject’s action or state of being in this photo.

- List 10 or more emotions to describe the subject’s action or state of being in this photo.

- Create a caption using only emojis.

- Caption this in five words.

Do you need photo inspiration? We love the New York Times.

Brainstorming bell ringers

Sometimes a five-minute brain dump is all you need to break out of a slump.

- Looking at the school events calendar for the week, list different approaches you could take to cover each event in a table labeled before, during, and after.

- Design a unique “map” page showcasing the school campus and highlighting key locations, such as classrooms, the cafeteria, and outdoor spaces.

- Create a visual timeline of major school events throughout the year, using icons or symbols to represent each event.

- List 10 “hacks” that make school easier for you.

- Create a mini infographic showcasing interesting statistics or facts about an aspect of the school year.

- Design a series of icons or symbols to represent different academic subjects, extracurricular activities, clubs and organizations, and sports teams in the yearbook.

- Sketch a “Behind the Scenes” spread showcasing the yearbook team’s work so far.

- List teachers, labs, projects, field trips, and assignments that challenged you to think creatively or outside the box.

- [Display unused yearbook photos of note in a “Yearbook Story Idea” station.] Consider uncovered aspects of the school year and brainstorm three ways to get them in the yearbook.

Use these bell ringers to model a yearbook critique

Every student (and adviser) who helps produce the yearbook puts their work on display. No other group of students’ homework is hanging around 10, 20, or 50 years later like a yearbook. Boom. That said, use these critique prompts to reinforce positive comments.

- [Display a spread] Sketch the layout and identify each component (e.g. gutter and caption).

- List the elements we used to create a sense of unity and flow throughout the yearbook. What are there recurring visual motifs or elements that tie the pages together?

- [Display three spreads from your yearbook] Give five specific examples of how these spreads carry out our theme.

- Using an in-progress spread, give five examples of how your design connects to the remainder of the yearbook.

- [Display a spread] Sketch the layout. Identify the primary and secondary design elements and explain whether the hierarchy of information is clear.

- Reflect on a memorable moment from a previous yearbook. Analyze the elements that made the module, spread, or story engaging.

Two things:

- Start with examples of strong design from your students to highlight the wins.

- Keep it technical. When students use terms like eyeline, dominance, and alignment, there is a specific element to which we can attend versus “I don’t like it.”

Writing prompts for reflection

Sometimes, students need time and space to be introspective. These bell ringers are less about the how of yearbook and more about the why. After answering them in class, try using them for interview topics for other students to use in personality profiles or sidebars.

- If you could give one piece of advice to future students, what would it be and why?

- What is one thing you learned about yourself this year that you didn’t know before?

- Describe a moment when you felt proud of yourself and explain why it was significant to you.

- If you could choose one word to summarize your overall experience in this school, what would it be and why?

- Share a story about a time when you overcame a challenge or obstacle and what you learned from it.

- Describe a teacher or staff member with action words and explain how they influenced you.

- Share a funny or embarrassing moment that happened to you during the school year.

- Share a piece of advice you received from someone that changed your mind.

- If you could create a new school tradition, what would it be and why?

- Describe a time when you felt like you made a positive difference in someone else’s life.

- What is one thing you wish you had known as a freshman/sophomore/junior that you know now as a senior?

- Describe a moment when you felt like you truly belonged and were part of a community.

- If you could interview any historical figure, who would it be, and what five questions would you ask them?

- Share a piece of advice you would give to incoming freshmen and explain why you think it’s important.

- Reflect on a moment when you felt inspired or motivated by someone else’s actions or achievements.

- Share a quote or motto that has guided you throughout this school year and explain its significance to you.

- If you could go back and change one decision you made this year, what would it be and why?

- Describe a meaningful friendship.

- Reflect on a time when you had to step out of your comfort zone and how it contributed to your personal growth.

- What would you want to ask or know about your future self?

- Describe a memorable moment from a school event or celebration and why it was special to you.

By choosing to incorporate bell ringers, you’re optimizing instructional time by utilizing the initial minutes of class effectively. By engaging students immediately, you’ll minimize transitional periods and idle time, ensuring that yearbooking (and learning) begin promptly.

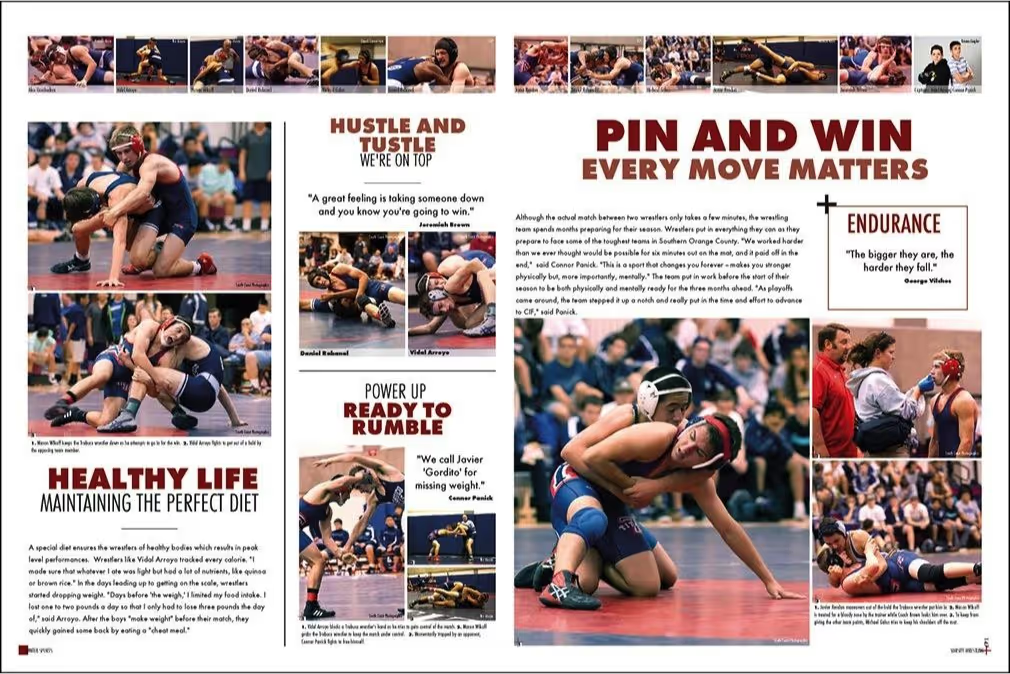

28 clever headlines to use in your winter sports spread

Wrestling

This yearbook page shows several headlines that work well for a wrestling spread. A number of bold headlines make a statement while still bringing the main headline “Pin and Win: Every Move Matters” to the reader’s immediate focus. The other titles maximize rhymes and take advantage of sports lingo: “Hustle and Tustle” and “Pin and Win” both rhyme and make references to wrestling jargon.

Here are some other fun slogans you can use for your school’s wrestling spread:

- “No Pain. No Gain”

- “Ready to Rumble”

- “Rock Solid”

- “Pin It to Win It”

- “Out on Top”

- “Toughest Six Minutes There Is”

- “Grapple Up”

Swimming

In this yearbook layout, “Staying Afloat Through Changing Times” is an engaging headline that both cleverly references swimming and makes the reader curious to know what changes have happened. The “Press Play” headline complements the film roll aesthetic of the photos next to it.

For more swimming spread-related slogans, check out some of our headline ideas:

- “Instant Athlete: Just Add Water”

- “[Your Team Name] Made Waves”

- “Sink Or Swim”

- “Life In The Fast Lane”

- “[Your Team Name] Made A Splash”

- “Dive Deeper”

- “Testing The Waters”

If you want to get your readers paying more attention to your main story, dig into your theme, your school’s culture, and sports terms to find ways to add a dose of clever to your winter sports spreads. It’ll help you steal a smile from your reader or unify your theme across multiple pages. In short, it’s worth the creative effort.

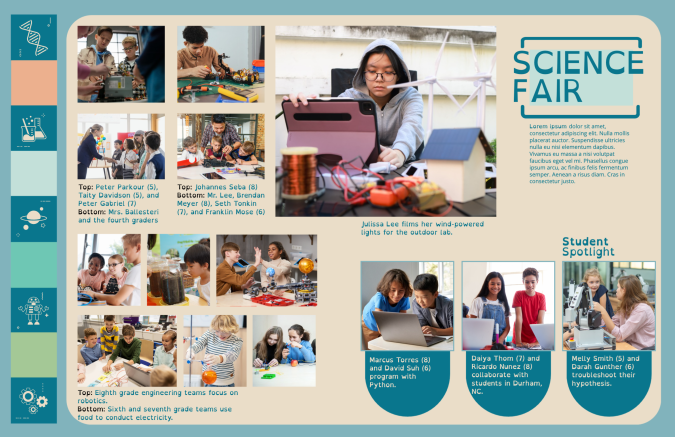

65 academics headlines for yearbook

Your academics section needs stronger headlines. Agreed? The headline on each yearbook spread influences the reader's scanning behavior. (Read: it makes buyers look at your hard work.) When skimming a spread, the eye is naturally drawn to the headline first, and from there, it can guide the reader to other important elements such as subheadings, captions, and images. While headlines traditionally are larger text, additional design elements such as type treatments and mixed fonts help also set them apart. Below are the why, how-to, and 65 examples of headlines you can use in your yearbook.

How to write captivating headlines

It’s easy to drop football or science fair at the top of your yearbook spread. For those looking to up their writing game, crafting journalistic, punny, or thematic headlines can enhance your yearbook storytelling.

Not sure where to begin? Use some of the academics-centric headlines below to inspire or jumpstart your writing process.

STEM headlines

- Calculating the Memories

- Chart a Force

- [Mascots] Count Get Enough

- Easy as Pi

- Formula for Fun

- Here Comes the Sum

- In Our Prime

- Make Sum Noise

- Massing Around

- On this Equation

- Pi-ous Celebration

- Rule for Thought

- Square One: [Year]

- Squaring Is Caring

- The Final Equation

- The Sum of [Year]

- Up and Atom

- Write Angle

Humanities headlines

- Act your Page

- Anything Prose

- Blurb the Line

- Bookmark my Words

- Born and Read

- Bursting at the Themes

- Do the Myth

- Full Theme Ahead

- Get Booked On

- Go for Baroque

- Move in the Right Direction

- Plot it Down

- Prose and Cons

- A Rhyme a Dozen

- Setting Pretty

- Strike a Prose

- The Write Stuff

Arts headlines

- All Hands on Deco

- All Strings Considered

- Band New

- Band Over Backwards

- Bright of Passage

- Brush with Greatness

- Canvas of the Year

- Choral High Ground

- Emboss Level

- Face the Music

- Fair and Snare

- Fluid for Thought

- Hip Hop to It

- Horn to Fly

- Rhythm and Reflection

- Size the Day

- Soul in One

- The Stage is Set

Senior section headlines

- A Class Act

- A Degree of Fun

- From Student to Scholar

- Looking Grad-ulous

- Making Moves

- Onward and Upward

- Rising to the Challenge

- Stepping Into New Horizons

- Taking Flight (good for a bird mascot)

- The Final Exam

- The Final Lap of our Academic Race

- The Future Begins

This is the trick to a great yearbook principal message

When it comes to the yearbook principal message, there’s a trick we often see with the best ones:

Involvement from the yearbook adviser.

We know that might sound a little odd, since your principal is the head honcho, and, let’s face it, none of us like to tell our bosses what to do (#Awkward). But the trick to a really good yearbook principal message isn’t just to let your principal write whatever it is he or she feels like. It’s making sure you help shape that message.

Think about it: You’re the expert on the yearbook. You know the book’s theme, and how it’s being carried through on all the pages. Your principal doesn’t. That makes your viewpoint a good one for the principal to hear. Look, we know that every yearbook adviser is going to feel a different level of comfort when it comes to telling your principal what to write. If that’s not for you, there’s another way to help. Helping them how to shape what they want to say. And that’s what the rest of this post is about.

Read on, and we’ll explore the most important aspects to writing a good yearbook principal message.

6 tips for writing a better yearbook principal message

1. Start with a story.

Did you know that there’s science behind storytelling? Seriously. Our brain actually reacts differently when it receives information as plain ol’ data than it does when information is delivered in a story-like format. That doesn’t mean a principal’s message needs to start with “Once upon a time…”It simply means that using more adjectives, including metaphors and sharing personal anecdotes are techniques that help a message connect with the reader—so start your message with a story.

2. Connect to the theme.

There is a lot going on at your school, right? That’s exactly why your yearbook has a theme. The yearbook theme serves as the unifier between all the clubs, activities, sports and classes that take place throughout the year.So it makes sense that, as the leader of the school, your message both unifies and sets the stage for that theme. Plus, tapping into the theme is a way to recognize the hard work of your yearbook team -- and a subtle way of supporting them.

3. Write like you talk.

This is your principal's message, and it should sound like them. Don’t be afraid to let your personality shine.Avoid long words, formalities and clichés that wouldn’t be part of your vocabulary in everyday conversation. One of the benefits of keeping your language simple is that it will be easier for readers to remember and connect with your message. And that’s exactly what you want.

4. Show gratitude.

Remember to thank the people who worked really hard to make the yearbook—and the school year—amazing. This recognition of a job well done goes a long way, especially if you rely on a group of volunteers throughout the school year.

5. Be concise.

Attention spans are shorter than ever. For most people that means shorter than a goldfish.There’s a better chance that people will read your message if they can see that it won’t take much of their time.

6. Find an editor.

This is where you, the yearbook adviser, get to play a really big role again.Once your principal has created a message they're happy with, it's your turn to step in, and give it a good edit. Check for the other five tips, then proofread it. Doing so will ensure that their message is clear and error-free. It's the best way to make your principal's message stand out (and to save them unwanted embarrassment).Your yearbook principal message isn't just the responsibility of the principal. And it's not just letting your principal write whatever it is he or she feels like. You need to step in and help shape that message. If you use these tips, your principal will deliver his or her message better than they would have done on their own. And that'll make you a hero.