Erikalinpayne

November 18, 2025

2

Min Read Time

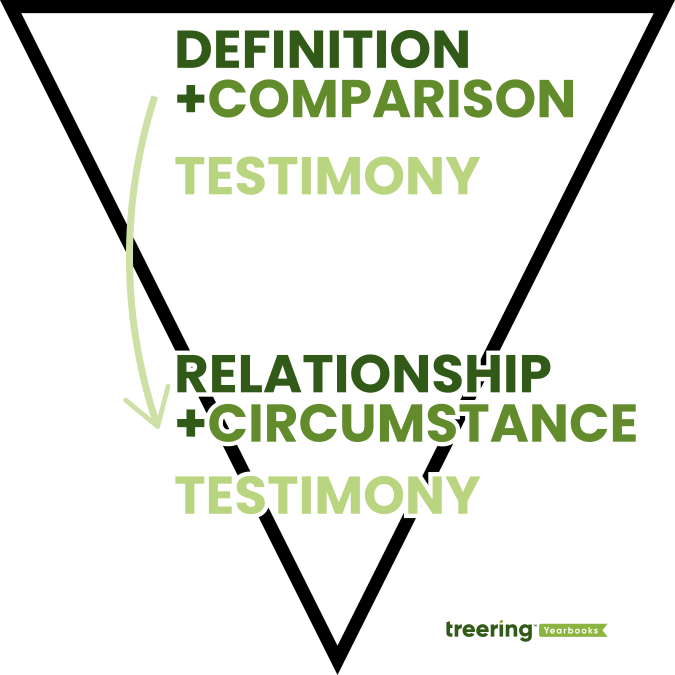

The inverted pyramid is the go-to launch point for budding journalists. (Anyone else hear a journalism teacher’s voice: “Don’t bury the lede!”) For these emerging writers, filling each level equates to squeezing the five Ws into its ranks. This could lead to repetitive or restricted writing. The “easy” fix: asking better questions.

Integrating the five common topics with the inverted pyramid structure helps students create engaging yearbook copy because it models inquiry. They move beyond “What was your favorite…?” They create questions with analytical depth. They craft stories worth reading.

How would the ancient Greek and Roman orators write a yearbook story? (That might as well be under “Adviser questions I’ll never ask for 1000, Alex.”) The five common topics are definition, comparison, relationship, circumstance, and testimony. The early scholars used this method of inquiry to discuss, persuade, and analyze. Developing yearbook interview questions based on the five common topics can be a structured way to gather information and insights.

The five Ws fall here: the topic of definition breaks down your subject into key components. What it is and who does it. Where it takes place. Why it’s important. When it occurs.

This is extremely helpful for students when they craft copy on an unfamiliar topic. For example, most people use “bump, set, spike” somewhere on a volleyball spread. We don’t bump. We pass.

Each game, dance, movie night, and fun run is unique. So are labs, presentations, debates, and study sessions. Find out what sets this event or activity apart. By defining what it is holistically, you are also defining what it is not: just another day. (Remember, there is a reason for this story beyond an opening in your page template.)

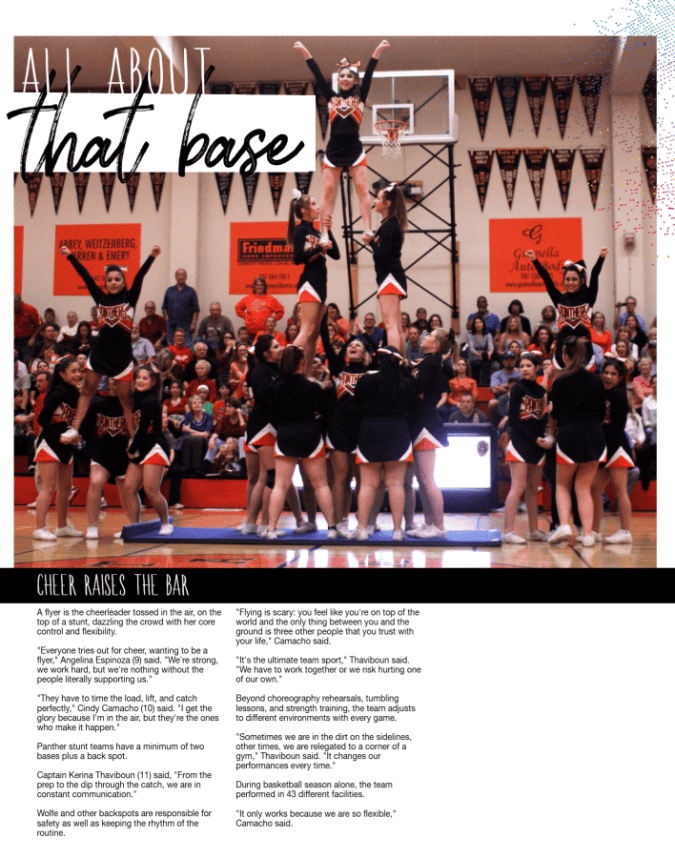

Sports and arts copy can always be improved by understanding the technique. Start with your photos and ask the stakeholders to explain what they are doing step by step. Define tools, from cleat spikes to microscopes, and their use.

Back to our volleyball example: She’s aligning her feet to the setter and positioning her body so her belly button is behind the ball. Straight arms and little-to-no movement are key for her to give a high pass the setter can push to the outside hitters or run a quick hit from the middle. She starts each practice by passing 50 free balls as an offense-defense transition drill.

No bumping is involved.

The next step is to expand upon the basics by drawing parallels or highlighting differences. Using analogies, journalism students can make complex ideas understandable. Sometimes, it helps to take the opposite approach and point out key differences.

Familiarity is comfortable. By relating new topics to known ones, you can ease your reader in.

Again, even though chemistry class repeats the gummy bear lab annually, it is not the same year after year. The same can be said about an AP class preparing their art portfolios or a Link Crew orientation.

Using the topic of comparison, student reporters have a reason to cover recurring events–they are digging into the differences.

Keyword: enhance. Comparison is valuable if it adds value. And before you flinch at the intended redundancy, remember new writers need to evaluate their notes as part of their process. Listing related and opposing concepts will also strengthen the topic of definition.

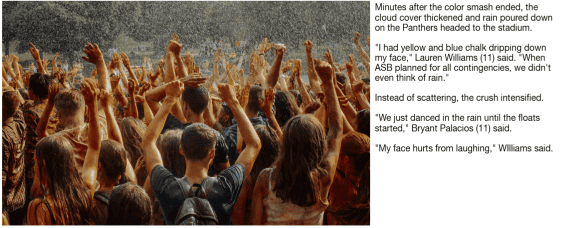

I’m combining topics three and four. Event sequences, cause-and-effect relationships, and the outcome of the event all have a place at the proverbial table. Understanding circumstance helps in tailoring yearbook copy to be more relevant and effective because we use it to examine the context of each story. It’s the here and now. These details help readers understand why the event is significant at this moment.

More than the water bottle du jour, the timeliness of a yearbook story gives its place in your school’s historical record. You give campus events context by relating them to the community or even the world.

In the example above, a student gave a speech. This is a daily occurrence around the globe. The author used the subject’s reported challenges and testimony (spoiler alert: that’s topic #5) to illustrate what led to the moment.

Chances are, this story wouldn’t have been printed in your mom’s yearbook. The circumstance was different.

Part of contextualizing your yearbook stories is adding what resulted from the story. Did the fundraiser set a new record? Athlete return for her final game of the season? AP Language class win the literary food festival? Wrap up your story.

“Give me a quote for the yearbook.” Next to definition, testimony is the most commonly used of the five common topics. It’s the human element. Including testimonies from different sources helps balance the story, gives authority to student writing, and showcases varied perspectives.

While it’s the fifth topic, when students write, they should incorporate the questions below.

Scores, stats, fundraising figures, and meaningful quotes enhance credibility and give voice to yearbook copy.

The short answer: ask more questions. How do you find out what is true and who do you ask? (This could be more common with sporting events over bio labs.)

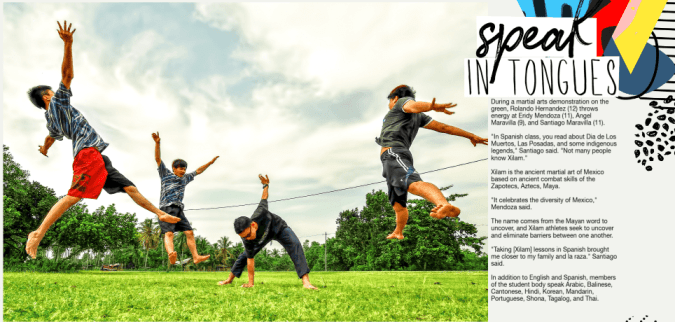

Let’s start with this photograph of four students on the green.

To come up with the copy, students identified:

This structure delivers both the essential information layered with insights. It moves beyond a listing of the 5Ws because it begins with inquiry.