Most popular

Subscribe to our blog

Most recent

Yearbook design tips: The golden ratio

In Dan Brown’s popular book, The Da Vinci Code, Harvard Professor Robert Langdon sets out to solve secret codes and messages related to the golden ratio. While the book is a work of fiction, there is science to the importance of the golden ration in design.

Rumor is the Egyptians used it to build the Pyramids, Leonardo Da Vinci himself was a scholar of its applications, and modern day financial markets create models around it. Designs built around the golden ratio are said to be the most pleasing to the eyes.

So, what exactly is the golden ratio, and how does it apply to yearbook design? Without completely getting bogged down in complicated math, think of it as a rectangle with length (side B) roughly one and a half (1.618) times the width (side A).

In an interview in Science Daily, Duke University professor, Adrian Bejan, explains why the golden ratio is so pervasive in art and design:

When you look at what so many people have been drawing and building, you see these proportions everywhere. It is well known that the eyes take in information more efficiently when they scan side-to-side, as opposed to up and down.

Bejan goes on to explain that animals have evolved their vision to scan for danger from side-to-side, or along a horizontal plane. Predators and danger typically come from behind or the sides and almost never from above or below.

As animals developed organs for vision, they minimized the danger from ahead and the sides.

If you’re interested in reading more about Bejan’s connections between nature and the golden ratio, he has a fascinating blog.

There is a lot of debate surrounding the exact science behind why we gravitate towards design that follows the golden ratio, but what is known, is that we do love it. And what’s most important to us is creating more pleasing design, right? Let’s talk about a few yearbook design tips incorporating the golden ratio.

Creating a Rectangle

Let’s start with the easiest application: Building a rectangle. Choose the length of the rectangle’s short side. For this example, we’ll use 600 pixels. Now multiply 600 pixels by 1.618 to get a rectangle of 600 by 971 pixels. This rectangle follows the dimensions of the golden ratio.

Creating Golden Text Ratios

You’ll want your headlines to be in proportion to your body copy. In order to follow the golden ratio, simply multiple 1.618 by your body text size. For example, if your text is size 10, your headline will be 10 times 1.618, or size 16.

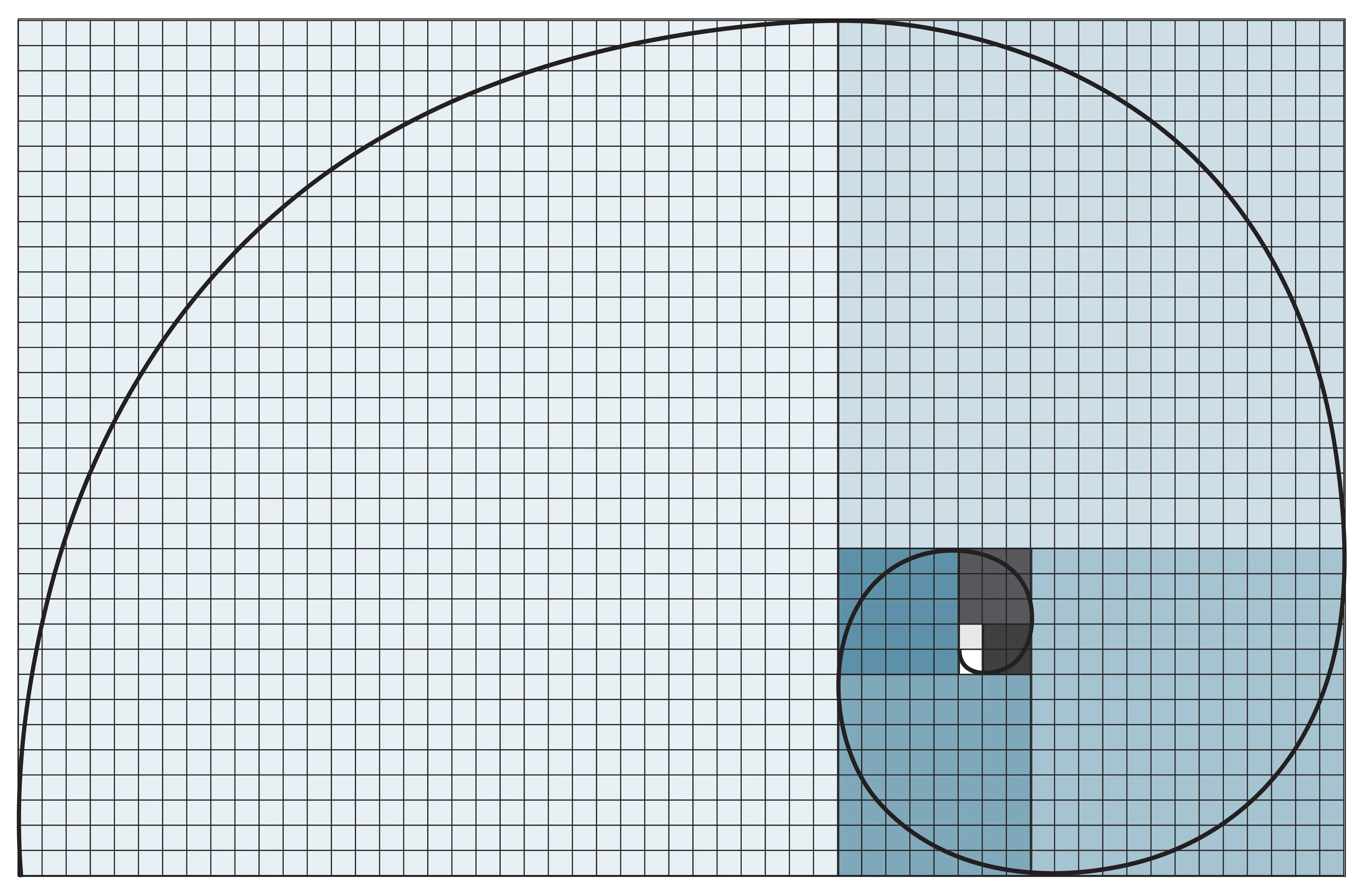

Fibonacci Sequences

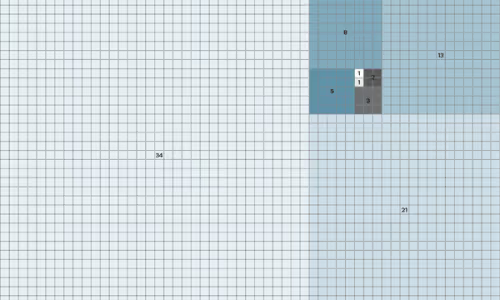

The simplest tool to creating design linked to the golden ration, is to use Fibonacci sequencing. Fibonacci sequences begin with 0 and 1. Add the previous two numbers together to get the next number in the sequence. 0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21…and so on. The image below is a good example of a creating Fibonacci sequence for page layout.

See how the page spread below, using Fibonacci sequencing, could create a very pleasing layout for your yearbook?

Why camera aperture is critical to taking good yearbook photos

If you’re a shutterbug like me, you’re always after the perfect yearbook photo. But perfect shots are relative to the elements and subjects we’re aiming at. If it’s a picturesque landscape in Yosemite National Park, we’ll want Bridalveil falls and all surrounding elements in focus. If it’s a ladybug perched on the petal of a yellow daisy, this time, we’ll want to draw the viewers attention to the insect’s red shape. And, like most yearbook photos, if it’s of a group of students, we’ll want to make sure all of their smiling faces are crisp and clear. When it comes to achieving these goals you’ll need to master depth of field. And you can only do it through use of your camera’s aperture.

What is the Aperture?

Simply put, the aperture is the physical opening in the lens that allows light to pass through. The wider the aperture opens, the more light can pass through. Want to know how to take yearbook photos, and for that matter, great ones? Master the aperture.

F-Stops

Cameras measure their aperture settings in what are called f-stops, written f/1.4, f/8 and so on. You can typically find the maximum aperture marked on the lens itself. What’s important to remember, is that a camera’s f-stop setting shares an inverse relationship with the the width of the aperture opening. Huh? In a dark room, with low lighting, by setting your camera to f/2.8 or smaller, you’ll be creating a very wide aperture opening, thus letting a lot of light in. A smaller f-stop number equals larger aperture opening. Remember this inverse relationships as I’ll refer to f-stop numbers for the rest of the post.

Large F-Stop Numbers

There is something else that happens by using different f-stops, and sometimes with dramatic effects. Depth of field. In the image below, the f-stop is set at f/8. Some professionals call this the “sweet spot” because it is the aperture setting that provides the sharpest focus for a lens. Notice how all of the elements of the photograph are in focus?

Small F-Stop Numbers

Now, let’s take it to the extreme by setting the camera on a wide open aperture setting (remember this means a small f-stop number). The photo below was taken by a lens with a maximum aperture setting of f/1.4. Notice how the baby’s eye is practically the only thing in focus, and that even her ear begins to “vanish”. This can create moody and dramatic effects with your photographs, especially for portraits or single elements.

Depth of field and the aesthetic quality of the blurred portions of photographs is such an important part of photography, that the Japanese have turned it into an art. They call it boke. Boke • BOH – KAY focuses on the parts of a photograph that are not in the current plane of focus. We see these areas as blurry or hazy in the final work. The following photograph illustrates the beauty of Boke. Notice how the background almost appears to be painted due to its smooth texture?

3 Tips for Using Aperture in Your Yearbook Photos

Let’s cover a few technical applications of depth of field depending on the subject matter in your yearbook photos.

Portraits

Yearbook portraits are probably one of the most common yearbook photos your school will capture. You’ll want to follow some key rules of composition, being certain that you are filling the frame with faces, but you’ll also want to make sure that the critical element of the photograph is in focus: The face. When taking portraits of one person, you’ll have a lot of flexibility in choosing your aperture setting. Be sure to focus on the subject’s eyes when using a low f-stop number (f/5.6 or lower).

Yearbook Setting Shots

When taking photographs of the school grounds and building, or of events and activities with large gatherings of people, be sure to use an f-stop setting of f/8 – f/11. This will ensure that the focus of all the elements in the photograph are sharp.

Yearbook Group Photos

The great documentary photographer, Arthur Fellig, when asked how he was able to capture critical moments of rapidly changing events, simply replied “f/8 and be there.” When taking group photos, you’ll also want to use an f-stop number of f/8 or larger. That way, the faces of all of your subjects will be sharp. This will also allow you to focus on your composition.

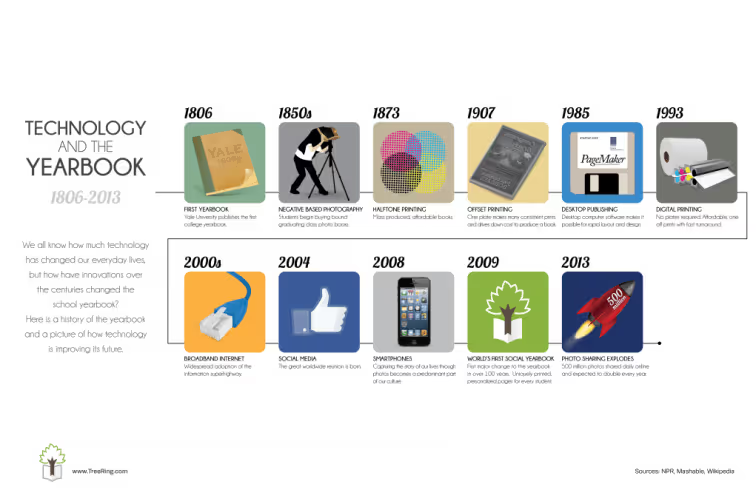

The history of the yearbook: How technology is reshaping it.

The History of the Yearbook Begins

We all know it’s a steadfast tradition in American schools, but what exactly is the history of the yearbook? According to a story by NPR, a Boston photographer named George Warren leveraged an advancement in photographic technology called the glass negative process to easily create many prints from one photograph. Warren encouraged his student subjects to purchase multiple portraits, share them with each other and then turn those collections of portraits into professionally bound books. The “Warren Yearbook” was born. The National Museum of History in Washington D.C. has the 1860 Rutgers College Yearbook on display, an example of a Warren Yearbook.

1900s and the Printing Press

The next big shift in the history of the yearbook came in the early 1900s with the invention and adoption of the printing press. Those books that were previously hand bound, one of a kind albums, could be mass produced with the creation of printing plates. Costs dropped, making the yearbook more accessible to schools and students from all walks of life. The stage was set for the growth of the traditional school yearbook

The Computer Age

Between 1985 and 2008 an explosion of technology brought on massive changes in the yearbook’s history, like desktop publishing, digital printing, social media and the widespread adoption of digital photography. The computer age disrupted almost every industry in the world including incremental improvements to the yearbook. Desktop software made it easier for schools to layout yearbook designs and digital photography provided a larger variety of shots from throughout the year.

The Social Yearbook

In 2009, with the mass adoption of social media and its prevalence as a part of the American culture, the yearbook made its first major shift in over 100 years. Digital cameras and innovations in online software make it easy for students and parents to create their own memories and add them to their uniquely printed version of the yearbook.

Yearbook Photo Ideas: 3 Tips On Composition

By improving the composition and lighting of your photos, you’ll be able to use any device with confidence. While drool-worthy mirrorless cameras are all the rage and DSLRs “look the part,” cellphones, tablets, and point-and-shoots can also produce great photos. The key is your perspective and awareness of the action.

Composition Basics

Composition creates compelling photos. When composing a shot, think about elements like background, framing, balance, leading lines, depth of field, and viewpoint. Even at sporting events or the school musical—when you’re limited on where you can stand—take some time to go through this list in your head to intentionally get the strongest photos.

In the digital age (did you read that in my grandma voice?), just clicking away and hoping for a usable image can be a waste of time. Being intentional for five to ten moments will help you anticipate action and yield more authentic images.

Background

If it’s not drawing the eye to your subject, you might want to get rid of it. Take time to assess what is behind your subject:

- If possible, remove distractions like garbage cans, signs, or other people

- At sporting events, stand on the opponent’s side so you get your fans’ reactions

- Position a photographer backstage or in the sound booth to capture behind-the-scenes action

Simple camera fixes such as adjusting the aperture (see “Depth of Field” below) or environmental ones (see “Leading Lines”) can help improve your photos’ backgrounds.

Framing

Your photos should focus on key interactions. For example, a tight frame on a student meeting their teacher on the first day of school captures a meaningful moment.

Alternatively, a wider frame might show the atmosphere of an event. Consider how close you want to be and what details you want in the shot.

If the event and space allow, move around to add diversity to how you frame your subjects. My yearbook adviser used to say, “Zoom with your feet.” It’s the second-best piece of photo advice I’ve received. (Lighting takes first billing for those of you playing along at home.)

Balance

While symmetry works well in group shots, you might also want asymmetry to draw the eye to a specific part of the frame. Think about how elements are weighted in the frame to achieve the mood you want.

In the example above, the laptop is what holds us captive.

Leading Lines

Use natural lines—like desks, edges of buildings, or stripes on the school bus—to draw the viewer’s eye towards the subject.

Depth of Field

This can be easily achieved with portrait settings on phones and cameras. Blurring the background adds drama and focuses attention on the subject. Whether you’re using a DSLR or a smartphone, depth of field, or aperture, can elevate your images.

Viewpoint

Experiment with angles. Try taking shots from above, below, or behind to add variety and interest. Different perspectives help tell the story more creatively and capture aspects that a straight-on shot might miss.

Lighting Essentials

To say lighting is crucial is an understatement. In photography, too much or too little light can impact the photo’s quality. Be aware of your main light source. If you’re at an event, take a moment to assess from where the best light is coming.

Tips for Indoor Photography

Windows can be problematic if they are behind your subject. Unless you are aiming for a silhouette, keep them to your side.

If the lighting isn’t ideal, adjust. Sometimes, just asking students to move to a better-lit area can make a big difference. They’re usually happy to accommodate. For example, if you are photographing a dance, set up an area to take group photos with good lighting.

Using flash can also help in tricky lighting. For instance, in a situation with backlighting (like a window behind your subject), a fill flash will illuminate the subject and balance the exposure. In low-light conditions, adjusting your camera’s ISO or shutter speed with the help of a tripod can also help capture the shot without losing detail.

Outdoor Photography Considerations

Outside, natural sunlight is ideal, and just like inside, positioning is important. Move so the sun is off to the side or behind your subject to reduce harsh shadows and prevent squinting. Most professional photographers avoid outdoor photoshoots when the sun is overhead for this reason. (Basically, when the fun run is happening.)

We recommend using a tripod and angling yourself so the sun is at your subject’s side.

Remember that a good photographer’s eye matters more than fancy equipment. Whether using a DSLR or a smartphone, focus on framing, lighting, and timing to compose meaningful moments.

This blog is adapted from Sandra Violette’s Photography session from TRL 24 POV: I’m on the Yearbook Team. Violette, a professional photographer and PTO mom, serves on the Onboarding and Engagement Team at Treering Yearbooks.